The Intentional Flaw

With edit inevitably comes release.

Last week, I wrote about the joy of clearing space—the quiet power of editing down to what truly matters.

This week, I’ve been thinking about what happens next: the release of the need for perfection.

It’s been showing up everywhere lately—the perfect posture I tried to hold in yoga, the perfectly worded follow-up email I wrote three times, the perfectly styled outfit for an event that I spent (literal) hours selecting for my Nuuly this month. And then I remembered something I learned while studying abroad in Paris: the idea of le défaut volontaire—the intentional flaw.

In couture houses, a seamstress might leave one stitch uneven. In Persian carpets, a weaver might deliberately break a pattern. Those imperfections weren’t mistakes; they were gestures of humility—and of humanity. They were the artist’s fingerprint, proof that the work was made by hand, not machine.

The Art of the Flaw

Artists have always understood the poetry in imperfection.

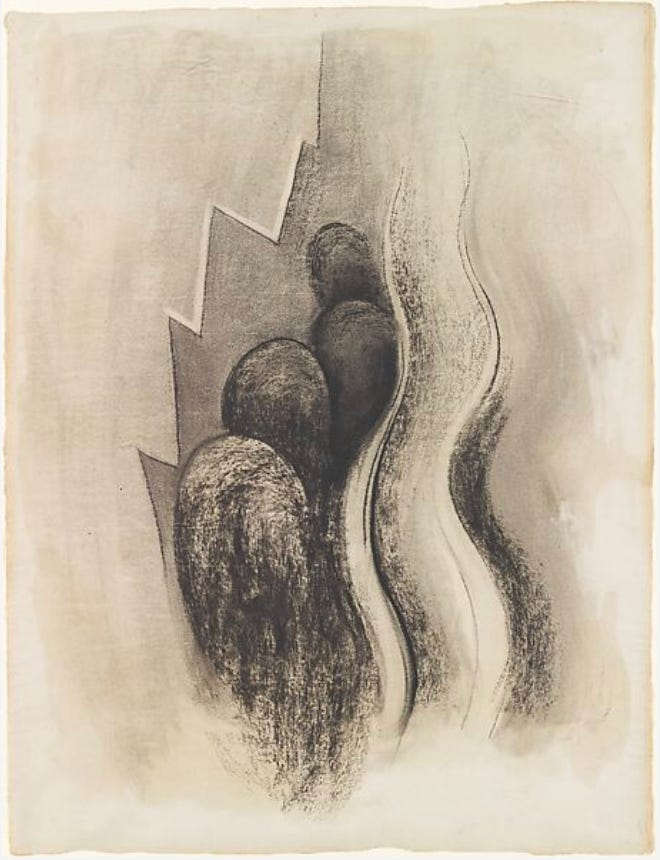

When Georgia O’Keeffe spilled water across an early charcoal drawing, she didn’t start over—she followed it. That accident led her toward the abstraction that defined her work.

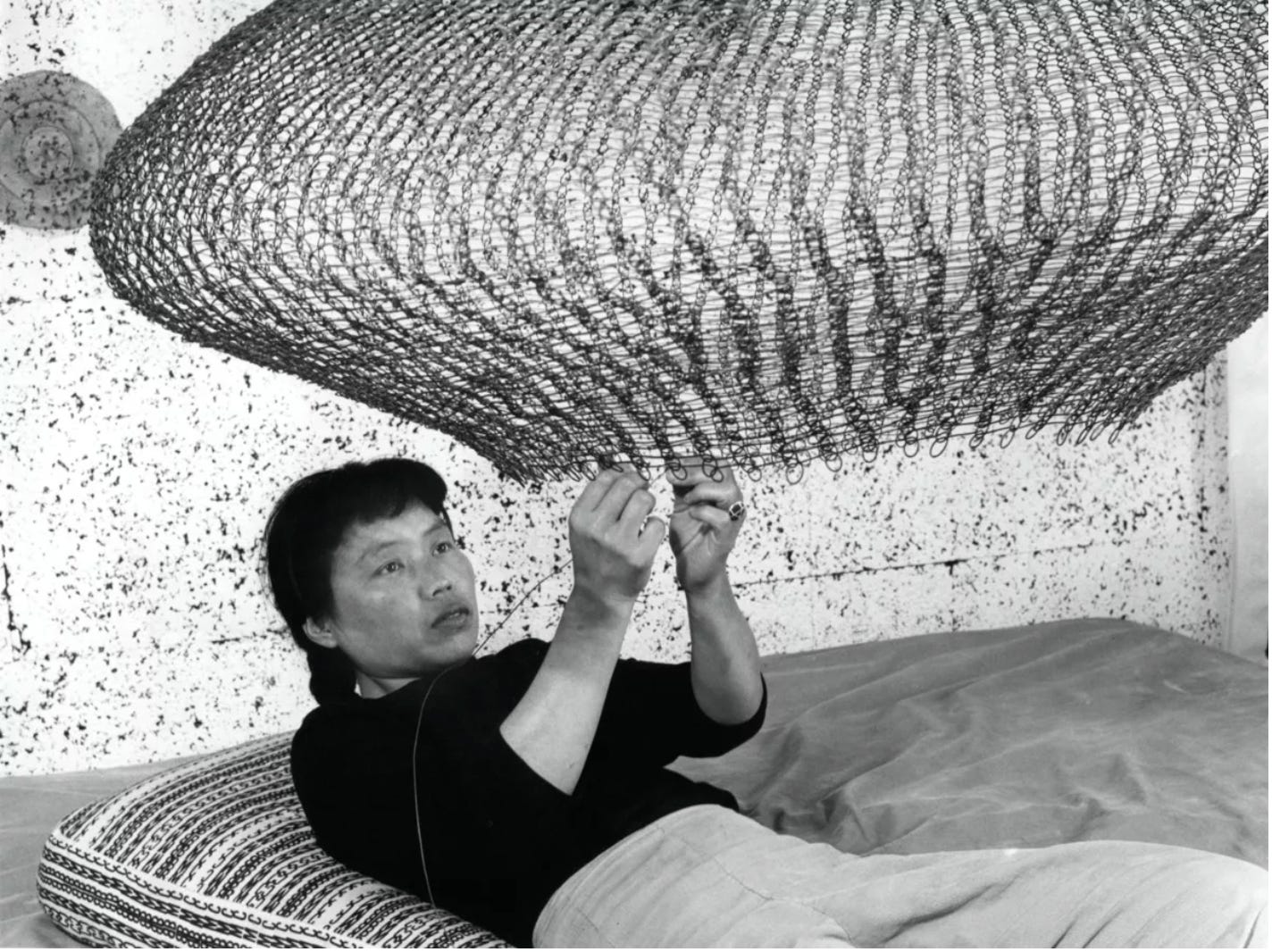

Ruth Asawa’s wire sculptures began as looping sketches that refused to stay uniform. Critics once called them too delicate, too feminine, too “crafty.” But those irregularities became her rhythm—forms that felt both fragile and fierce.

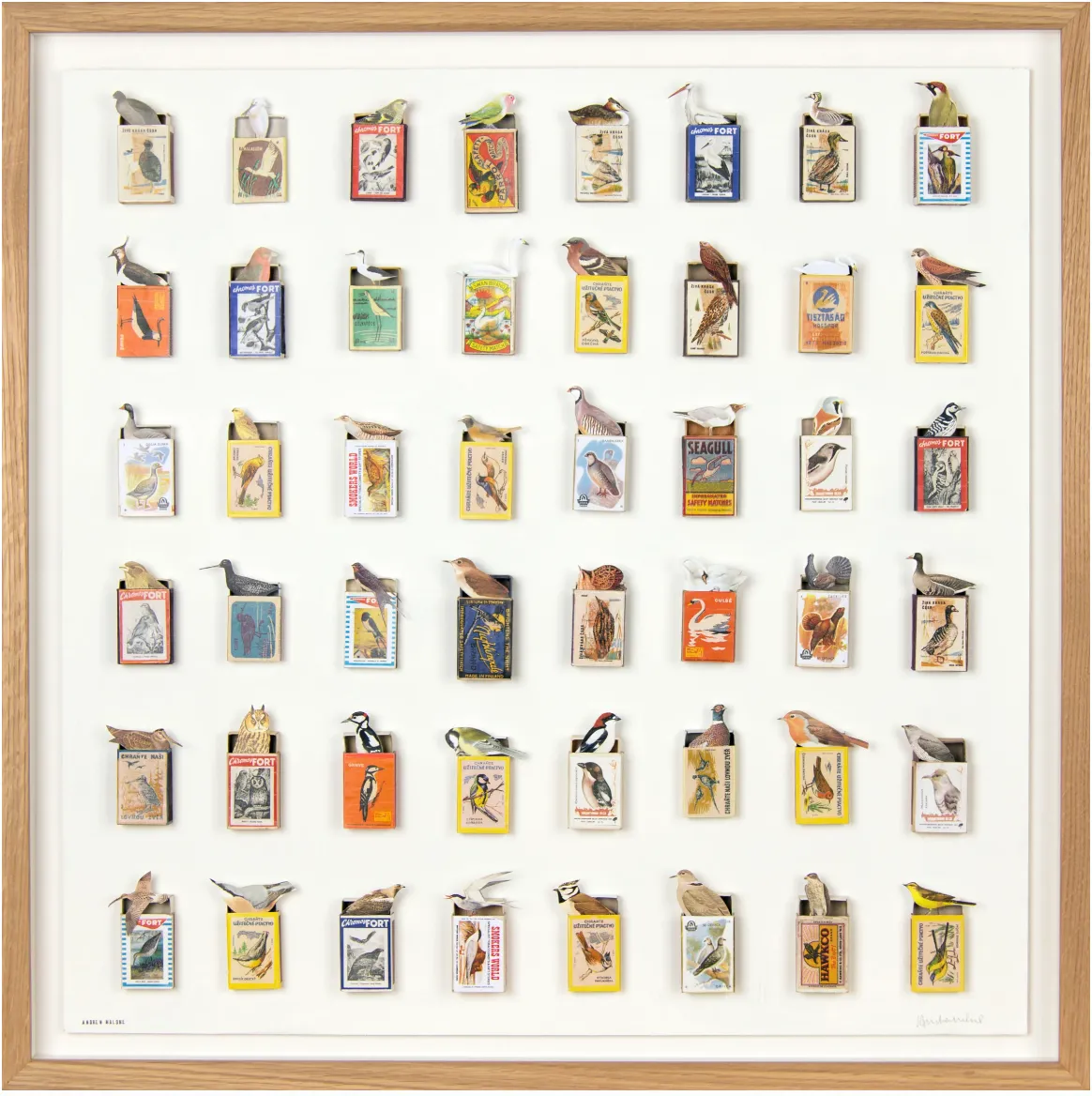

And El Anatsui, whose metallic bottle-cap tapestries shimmer across museum walls, once watched a piece collapse under its own weight. He didn’t force it back. He let gravity decide. Now, every installation folds differently—never the same twice.

“It fell into its own form,” he said. Sometimes that’s what perfection really is: when something becomes exactly what it’s meant to be.

The Performance of Perfection

Perfection often looks like devotion, but underneath, it’s about control. It’s a way of managing uncertainty—in art, in design, and in the way we compose our lives.

We edit, align, and polish until there’s no air left between the elements. It looks resolved, but it stops breathing.

As Brené Brown writes in The Gifts of Imperfection:

“Perfectionism is not the same thing as striving to be your best. It’s the belief that if we live perfect, look perfect, and act perfect, we can minimize or avoid the pain of blame, judgment, and shame.”

Perfection isn’t about excellence—it’s about protection. A shield we hold up against being misunderstood, overlooked, or not enough.

But imperfection is an act of courage. It’s the uneven brushstroke, the unbalanced form, the small, human fingerprint that keeps a space—and a soul—alive.

Kintsugi and the Beauty of Repair

The Japanese art of kintsugi holds this truth beautifully. When a vessel breaks, it’s repaired with gold, its cracks illuminated rather than hidden. Each line of repair becomes part of the pattern, proof that something was both broken and made beautiful again.

It’s not about restoration; it’s about recognition—a record of where the light got in, and how it stayed. There’s something deeply generous about that idea: that damage can become design, that imperfection isn’t something to hide but to honor.

Final Thoughts

Perfection promises performance and control.

Imperfection offers curiosity and connection.

We relate to what’s slightly off—the brushstroke that wavers erratically, the voice that cracks vulnerably, the story that resolves in an even bigger mess.

The pursuit of flawlessness isolates us. The embrace of imperfection brings us closer—to one another, and to ourselves.

Maybe that’s the reward of being human: to show up with the cracks visible, fingerprints and all, and still call it beautiful.

💌 Elle

P.S. What’s one imperfection—in your home, your work, or yourself—that you’ve learned to love instead of fix?

.svg)

.svg)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

-min.webp)