The Art of Time

Admittedly, this is the first article I’m writing well in advance.

As you read this, I’m very likely on a small plane being dropped into the Ecuadorian Amazon.

I’ll be off the grid for a week of artist sourcing and dream study with the Sapara, an Indigenous tribe known for their understanding of time not as a line, but as a living cycle.

It feels poetic to be writing about time while preparing to leave it behind.

In the book The Sabbath, Abraham Joshua Heschel writes that “we must not forget that it is not a thing that lends significance to a moment; it is the moment that lends significance to things.” He believed that modern life is obsessed with space—with building, owning, measuring—while the sacred exists in time: in the pauses, the rituals, the hours we inhabit fully.

I’ve been thinking about that distinction a lot lately.

In my daily life, time is something I schedule, track, and optimize. It’s a resource to be divided.

But in the jungle, there will be no clocks. No calendar invites or countdowns. Only light, humidity, and the cyclical rhythm of sound—the rustle, the rainfall, the night chorus.

The Design of Time

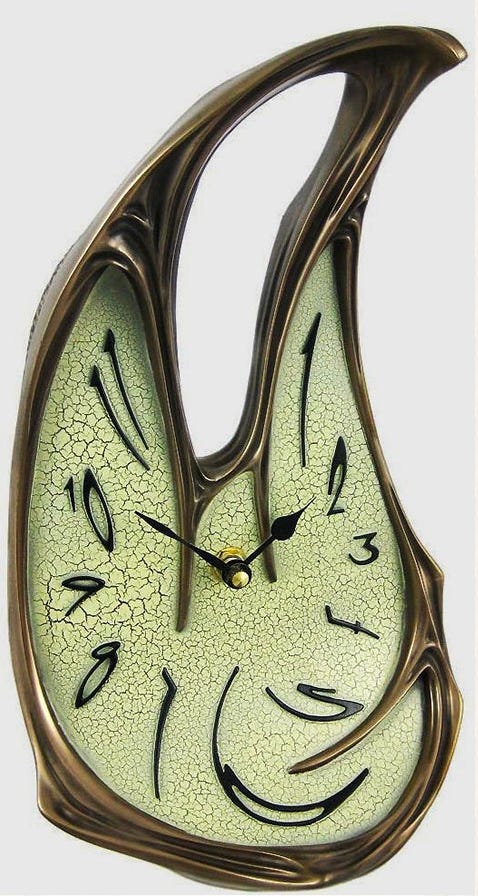

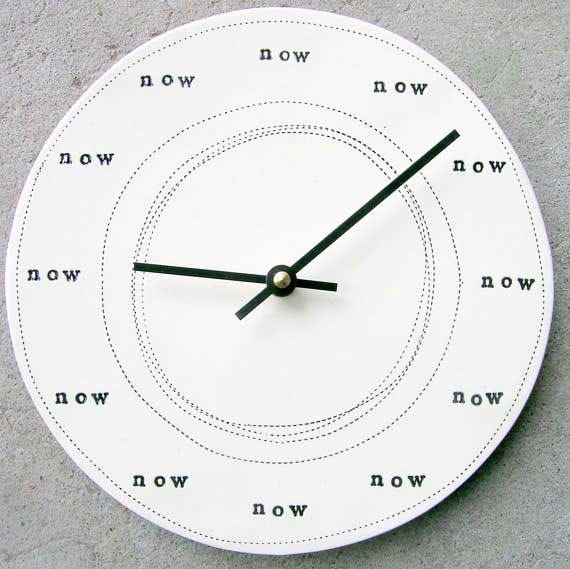

Clocks and watches are, in their own way, artworks of control.

Every tick, a small insistence that time is linear—that life moves forward in measurable increments. But design always reveals its philosophy: the circular face of the clock betrays the truth we pretend to forget. Time isn’t a straight line—it’s a loop, endlessly returning.

I think of how certain spaces seem to suspend time: a candlelit church in Lisbon, a salt-streaked ruin, the Water Lilies in Monet’s garden.

Monet returned to the same pond day after day, painting it again and again—the same water, the same light, endlessly changing. There’s something comforting in that circular repetition. It reminds me that even when life feels like it’s moving slowly or not at all, every small act of showing up accumulates. Over time, those quiet, consistent moments can become something extraordinary—a masterpiece, if you will.

Standing before those vast panels, you can feel it—the devotion, the patience, the slow expansion of time. Monet wasn’t painting a single instant; he was painting duration.

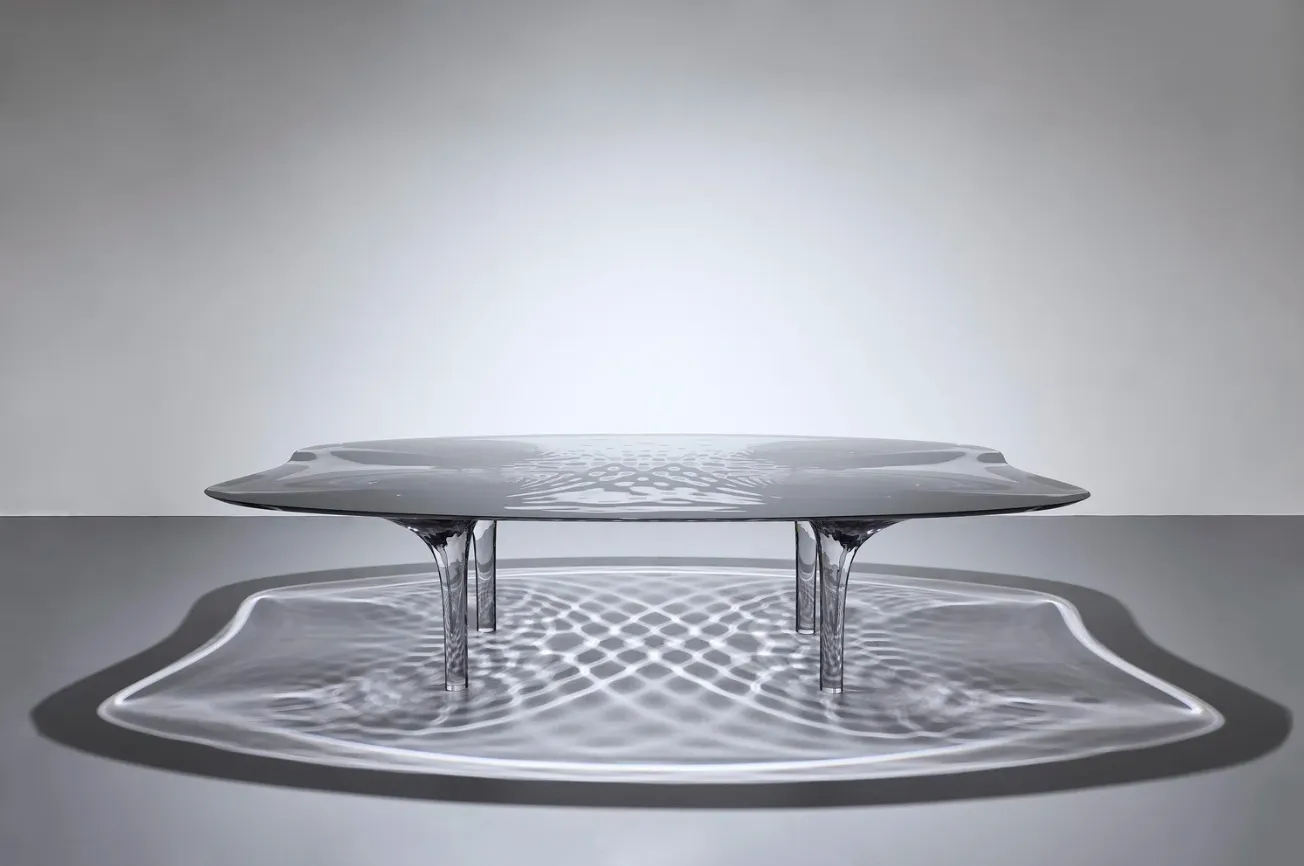

That’s what sacred design does, too. It loosens our grip on the clock and invites us into presence.

Time as Texture

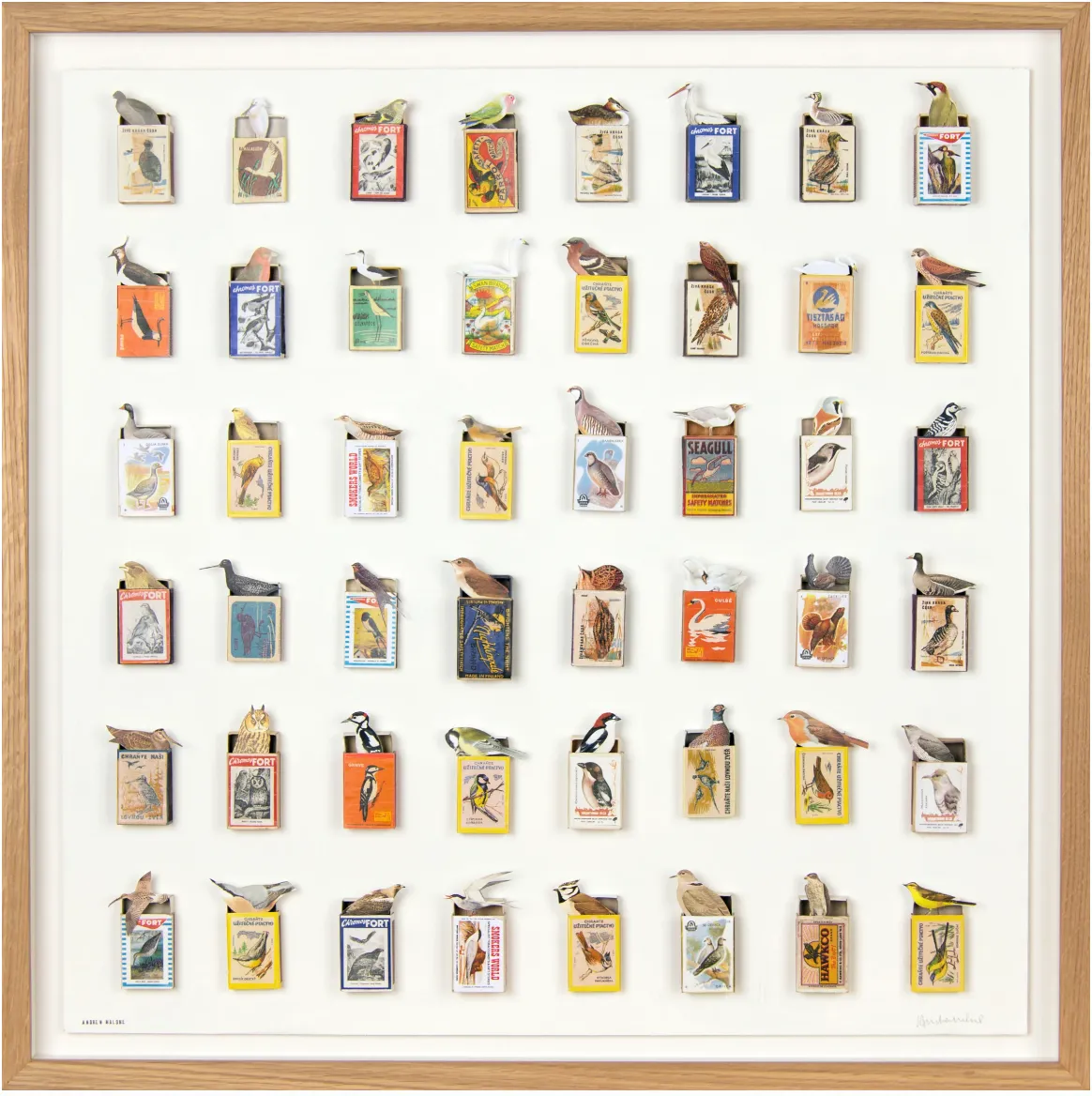

In design, we sense time not only through clocks but through materials.

A chair that’s been sat on for generations. The softened brass of a doorknob. The patina of touch is proof that time can beautify, not just decay.

Maybe that’s what sacred time really is—the moment we stop trying to capture it and simply allow it to leave a mark.

The Luxury of Slowness

Before I left, I found myself polishing my watch, then leaving it on the dresser. Not as an act of rebellion, but reverence.

Because maybe time isn’t the enemy of presence after all—it’s the material it’s made from.

💌 Elle

P.S. I’ll be off the grid this week—join me in spirit. Power down, wander a little, and let me know what finds you when you stop looking for the time.

.svg)

.svg)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

-min.webp)